Equity investors are still struggling to digest the extreme uncertainty triggered by the historic coronavirus crash. But it’s not too soon to start identifying some of the dislocations created by the downturn and potential implications for an eventual recovery.

In just three months, the outlook for equities has been transformed beyond recognition. When the year began, a thaw in the US-China trade war and recovering optimism over global macroeconomic growth set the stage for solid earnings gains. Within weeks, the novel coronavirus that surfaced in China spread across the world, throwing markets into disarray. Equity portfolio managers now face three concurrent challenges: piloting portfolios through the current extreme volatility, positioning for a now certain recession and thinking ahead to “the day after” the pandemic.

Investors have equally daunting concerns. Has the market reached a trough? After suffering painful losses, how long will a recovery take? And within equities, what’s the right way to allocate for uncertain times ahead?

Definitive answers will be hard to come by until the pandemic peaks. However, by asking the right questions now and drawing on lessons from past systemic crashes we can prepare for the challenges ahead.

Pandemic Prompts Historic Crash

During the first quarter, global equity markets plunged into bear market territory faster than ever before. The combination of a public health disaster, the ensuing macroeconomic shock and an oil market crunch exacerbated by a Saudi/Russian price war inflicted a severe blow to stocks.

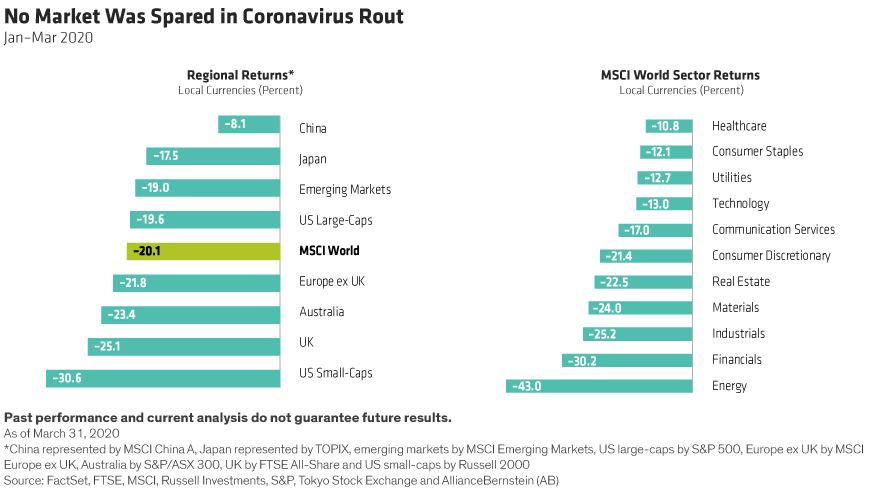

The MSCI World Index dropped by 20.1% in the first quarter (Display, left), in local-currency terms. From its February 20 peak through March 23, the index tumbled by 33.1%, before recouping some losses later that month after the US Congress passed a $2 trillion stimulus bill. Emerging-market stocks fell by 19.1%. In China, however, signs of success in quashing the virus helped reduce losses to 8.1%. While no sector was spared in the global sell-off, energy stocks and financials were hardest hit (Display, right).

Volatility Spike Squeezes Liquidity

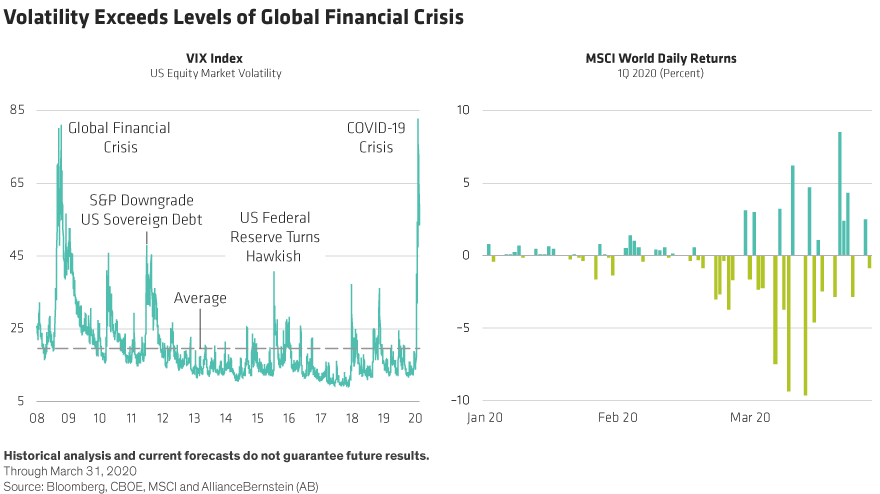

Volatility jumped above levels seen in the global financial crisis of 2008 as stocks swung wildly (Display). When the S&P 500 Index bounced back by 17.6% over three days through March 27, it was the biggest three-day percentage rally on record since 1933.

Violent market moves prompted a liquidity squeeze. Selling by systematic and quantitative strategies led to indiscriminate pressure on share prices. While equity portfolio managers were able to execute trades easily enough, widening bid/offer spreads pushed up trading costs dramatically.

In this environment, standard risk models performed poorly. That’s because risk models are based on recent historical data and have no close precedent for what’s happened. In many cases, companies whose stock prices are normally uncorrelated suddenly became correlated.

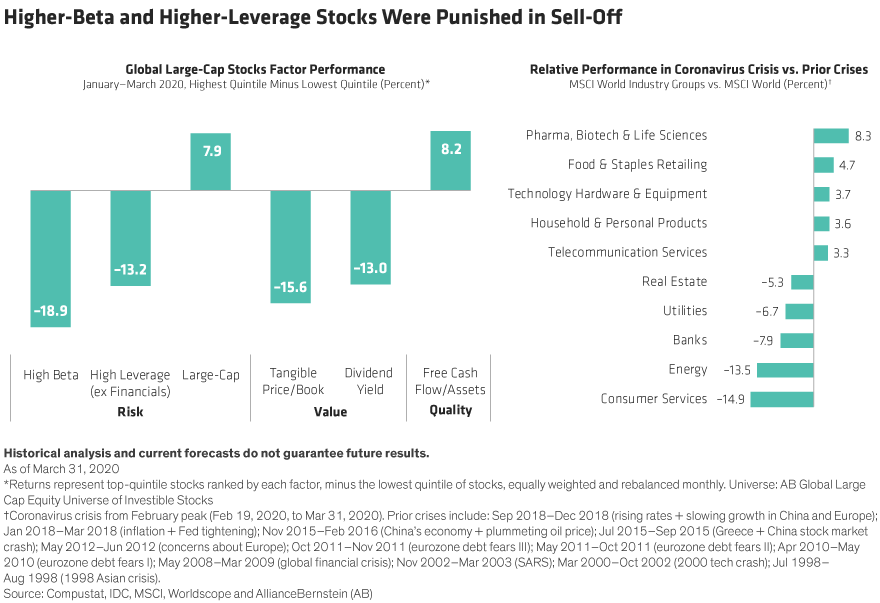

Which parts of the market held up better? Not surprisingly, lower-beta stocks and higher-profitability stocks fell less than the market. Stocks of companies with low leverage performed better than stocks with higher leverage (Display, left). Growth stocks outperformed value. And large-cap outperformed small-cap.

But stocks with high dividend yields, which are typically seen as defensive, underperformed the market amid concerns that companies may cut payouts. Some industries that were resilient in past downturns, such as real estate and utilities, didn’t protect portfolios to the same degree as in the past (Display, right).

Aggressive Policies Launched to Counter Recession

A global economic recession is now underway. What began largely as a supply-chain disruption emanating from China has morphed into a simultaneous global supply and demand shock as companies closed down and locked-down consumers stopped spending. But how deep will it be and for how long will it last?

The speed and size of the fiscal and monetary response of governments and central banks has been encouraging—and a welcome contrast to the 2008 crisis. It should limit the economic damage on the way down by preventing a widespread credit crunch and helping idled employees and otherwise viable businesses stay afloat. However, economies can’t normalize—and company earnings can’t recover—until the virus is brought under control and something approaching normal life resumes.

China’s experience offers some hope as the world’s second-largest economy started getting back to business in late March. As the world wrestles to control the virus, investors can watch China for some clues of what shape the recovery might take.

Earnings Fog Creates Valuation Confusion

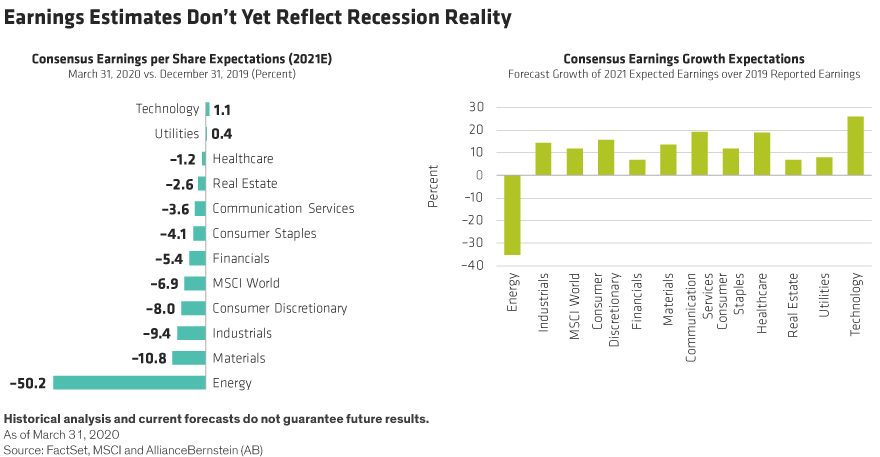

Companies are just beginning to figure out how their businesses will be affected. By quarter-end, few companies had provided forward guidance on earnings. So even though consensus estimates have come down during the quarter (Display, left), they don’t yet reflect the impact of a sharp recession, in our view. Indeed, earnings growth forecasts for 2021 versus last year’s reported earnings are still positive (Display, right).

How far might earnings decline? A recent note from an AB sell-side analyst provides a possible estimate of the size of the likely hit to US earnings. It suggests that US earnings will likely contract by 36% in 2020 and then recover by 33% in 2021, assuming the lockdown does not last for more than one quarter. This would imply the US equity market is currently trading on 17.5 times 2021 earnings, in the range of the last 10 years but not a recessionary trough.

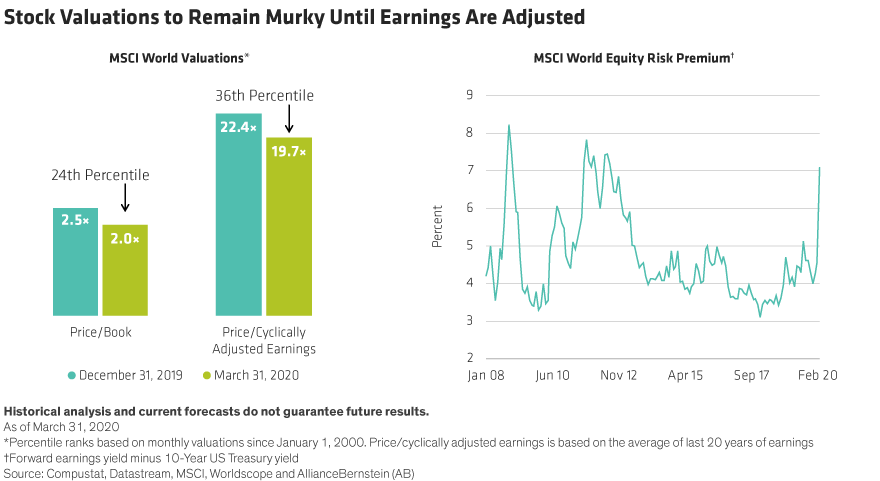

Similarly, valuations for global equities are below historical averages (Display, left). But as earnings continue to decline, valuations could compress further before reaching extremes, in our view. Still, we believe that equities do look attractively valued compared with bonds after the sharp decline of government bond yields, with the US 10-Year Treasury yield down to 0.68%. The global equity risk premium was 7.1% at the end of the first quarter—the highest since August 2012 (Display, right).

Considering Multiple Recovery Scenarios

Equity investment managers cannot wait until earnings forecasts are updated to evaluate holdings. Since it’s too soon to have confidence in a single scenario for macroeconomic and earnings growth, it’s important to understand how company cash flows will behave under different scenarios.

These could include a V-shaped recovery—a sharp economic downturn followed by a speedy bounce. In a U-shaped recovery, demand remains subdued at low levels for some time before a rebound gathers momentum. It’s also possible that the cycle will be uneven, with countries returning to work as the virus is subdued but forced to impose lockdowns again when a second wave hits. This has already happened in places like Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore.

Stress Testing Balance Sheets

Applying scenario analysis to company performance starts with the balance sheet. Solvency will determine which companies survive and which perish in the economic shutdown. Balance sheets must be tested for their ability to hold up in downturns of differing durations and in revenue reductions of differing magnitudes.

Severe bear case scenarios must be taken seriously. Even as we search for signs of hope, the world is now in unchartered territory. We simply don’t know the full impact of such a broad, indefinite economic shutdown. We don’t yet know how fiscal actions will help stabilize industries. So, higher-risk companies should be carefully scrutinized for worst-case scenarios, and portfolio positions should be resized to account for heightened risks.

Reconstructing Earnings Scenarios

After sifting for balance-sheet weakness, fundamental research can focus on underlying businesses. Even before receiving management guidance, analysts can start to gather intelligence on a company’s earnings path.

This requires looking through the current uncertainty. In many sectors and industries, earnings in 2020 will be much lower than expected before the virus. Projecting ahead to 2021—in different global recovery scenarios—can provide important context on current valuations.

Winners and losers will be determined by industry dynamics and managements’ ability to make creative strategic decisions. Which companies can redesign global supply chains to repair broken links? What strategic advantages will allow companies to compensate for lost demand in unexpected ways? Is a company capable of cutting costs to support operating leverage through a recession? Will new business opportunities arise from the crisis? Addressing these qualitative questions lays the foundation for constructing meaningful cash-flow and earnings scenarios that will allow active investors to act on pricing dislocations when the time is right.

Dislocations Create Opportunity

Our portfolio teams report that nothing in the global financial crisis came close to what they witnessed in the last six weeks of the first quarter of 2020. When a company like Boeing can lose nearly three-quarters of its value in a month and then see its share price almost double in a week, it’s clear that markets are not pricing securities based on long-term fundamentals.

At times like this, discipline is paramount. That doesn’t mean portfolio managers shouldn’t make adjustments—for example, by reducing exposure to especially volatile or vulnerable names. But it does mean that portfolio managers with a growth, value or core investment philosophy should stay focused on their stock selection processes, even when it feels like the world is falling apart.

When share prices become disconnected from a company’s underlying cash flows, opportunities are often created. Investment teams that have a dispassionate framework for analyzing probable outcomes can spot these opportunities and move quickly to take positions when they arise.

Positioning for an Eventual Recovery

Investors, too, should be mindful of their vulnerabilities. In the face of a pandemic, running for the exits might seem reasonable. But by withdrawing from the markets after a steep collapse, investors lock in losses and forfeit the chance for recouping losses in an eventual recovery (Display).

We don’t know when the markets will recover. History suggests that after a decline of 20% or more, equity markets take an average of three years to get back to where they were. It’s too soon to say whether a recovery will be faster or slower than normal, as much will depend on how soon countries conquer the virus and reopen for business. Given the scale of the current crisis, we may not have reached the trough in global equity markets yet.

But eventually, a rebound will come—and every rebound is different. Following the dot-com bubble, many old economy stocks held up well. In 2009, beaten-up cyclical stocks, often with high leverage, led the initial recovery. Market leadership then shifted to the FAANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google). It’s too soon to predict what types of stocks will lead a future recovery. As a result, we think asset owners should maintain diversified equity exposure across styles and geographies to capture a potential recovery, whatever form it takes.

What Next? After the Virus

In the vortex of the virus, it’s hard to visualize what the post-pandemic world will look like. The disruption to supply chains may accelerate manufacturing changes that were already underway. The global model of company efficiency, focused on generating incremental revenues and profits with fewer assets and inventory, could be challenged in favor of more robust supply chains that may cost more to operate.

Consumer behavior and business models may change. Airlines, cruise ships and hotels may never get back to where they were before the coronavirus. Yet healthcare spending could increase and be directed to new areas of research and development. Technology enablers of remote working and learning could receive a structural boost. Investors should already be on the lookout for unexpected trends that could redefine the world and equity markets when the coronavirus is ultimately conquered.

Christopher Hogbin is Co-Head—Equities at AllianceBernstein (AB).

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams and are subject to revision over time.